If you’re writing a novel there’s one thing that, if overlooked, will cause you more grief, pain, and rewrites than anything else. It can even send you back to square one, requiring a total rewrite of a manuscript that you’ve already spent hundreds of hours working on.

It’s something Nicole Meier covered in a recent Note:

This matches my own experience as a developmental editor. The vast majority of novels I work on end up having to go back to the drawing board, and it’s almost always because the writer hasn’t followed any kind of structure.

Both story and scene structure are vital to creating the emotional reaction we want from our readers—keeping them gripped to the page ensuring they leave the book feeling satisfied, as though they’ve reached the end of the story they were promised. Structure is also indispensable if we want to attract an agent or publisher.

Far too many writers sink their blood, sweat, and tears into a manuscript, only to have to go back and do it all over again, wasting time, money, and costing themselves a huge amount of pain because they didn’t learn about structure in advance. So, we’re going to talk all about it and make sure that doesn’t happen to you!

Next week, we’ll be digging into the mechanics of scene structure, but for this week’s deep dive we’re zooming all the way out: looking at the various forms of story structure and how to use them in your work.

Structures are as old as stories themselves. They’re mythic. Archetypal. And they free our readers up to focus on what really matters: whether the protagonist will achieve what they’re fighting for, and how much it’s going to cost them.

As Above, So Below

When it comes to storytelling, everything has unwritten expectations—from the order of our adjectives to the developments that happen over the course of a trilogy, or even an entire series of books.

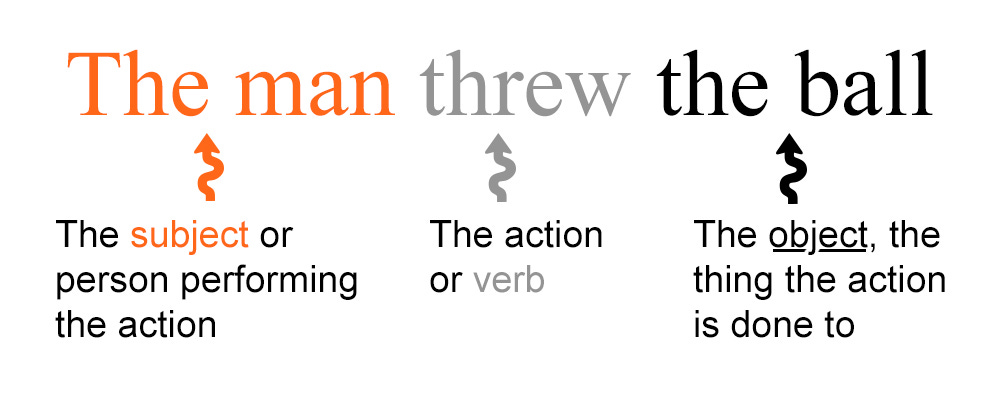

We see it in sentences, where the subject generally comes before the verb which comes before the object.

And while sentences might become more complex, or even occasionally break this rule, the further we stray from the reader’s unconscious expectations, the more effort it takes to understand.

The same is true with stories. Readers expect them to flow a certain way, with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

Importantly, there’s no single structure-to-rule-them-all. Different cultures, genres, and even individual writers will structure their stories in different ways: from the conflict-free Kishōtenketsu structure from Japan, to guides on how to write a compelling story without following a predefined structure at all. However, in all cases, the trick is to know exactly what we’re doing, why we’re doing it, and the effect it will have on our readers.

Obviously, we want to find the things that work for us, rather than imposing something we hate onto our writing. If you’re a planner, you might use your chosen structure in the outlining stage. If you pants your way through a story, it can be helpful to internalise the rhythm and beats of a particular structure beforehand, to make sure you’re adhering to it (at least roughly) as you work. If you really want to, you can even dump the entire first draft onto the page, then go back and rewrite everything to fit a structure later.

Either way, understanding how we work can help us make an informed choice, but knowing what story structure is, how it works, and why it’s so important will ensure you set off on the right foot.

Beginning, Middle, and an End—Why Structure Matters

Almost everything has an underlying pattern or rhythm—a flow that we expect without even noticing. Summer descends into autumn which darkens into winter. Listening to pop songs on the radio, we’re lulled by the familiar refrain of verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge. It helps us know what to expect, even if we don’t yet know exactly how things will pan out.

It’s almost comforting. It means that we understand the rough shape of something even before we’ve been through it, and stories are no different. Especially with genre fiction, readers almost never want to be completely blindsided—lost in a book with no idea of what’s happening or where it’s going to end up. Instead, their enjoyment comes from an intuitive understanding of the underlying pattern: the rise and fall that almost all stories have as a book establishes its premise (and its world), develops them, and ties everything up more-or-less neatly at the end.

Structures are as old as stories themselves. They’re mythic. Archetypal. And they free our readers up to focus on what really matters: whether the protagonist will achieve what they’re fighting for, and how much it’s going to cost them.

From the hero’s journey of legend to the more recent blockbuster movies, stories have always followed patterns.

In speculative fiction, the most common is the three-act structure, so that’s the one we’ll be focusing on for the remainder of this post. And while there are numerous different variations on it, they all have the same basic elements in common.

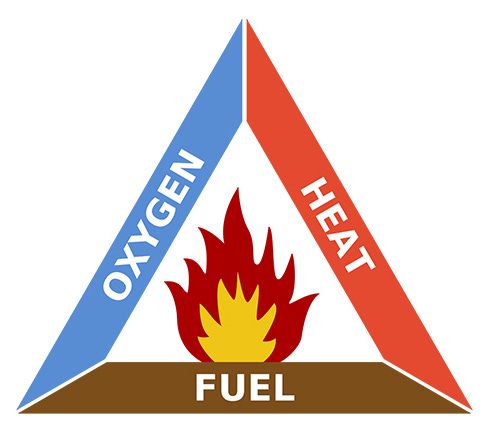

The Fire Triangle of Conflict

Just as an internal combustion engine (or any kind of fire) needs three equally important elements to get started, most stories require the same three things:

An interesting (and probably flawed) protagonist.

A goal that they want more than anything, and will sacrifice almost anything to obtain.

The obstacles and problems that arise and get in their way.

Our main character is the oxygen our story needs to breathe. Their goal is the fuel that sustains a novel from the first page to the last. And the obstacles are the sparks that light everything on fire and set the engine of story in motion.

Here’s an example of what that might look like in practice:

Evangeline is a reckless and hot-headed warrior who abandoned her family to pursue her dreams of adventure. Now her sister has gone missing and, driven by guilt, Evangeline will do anything to find her. Unfortunately, the shadowy cult who are ultimately responsible for her sister’s disappearance will do anything to stop her.

This isn’t a story structure yet, but it’s all the important elements that we need to build one.

Using the Three-Act Structure

Once we have our protagonist, their goal, and a conflict (or antagonist) to get in their way, we’re armed and ready to use the three-act structure.

It usually looks a little bit like this:

Act One is the first quarter of the book. This is where we put all of our pieces in place. After hooking the reader with something exciting, interesting, or unusual, we introduce our protagonist, develop the goal they’re going to pursue throughout the novel, and give the reader some idea of what they’ll have to overcome to reach it.

Act Two is twice as long as the others, and occupies the central half of the book—from the ¼ to ¾ mark. It involves a number of challenges and problems that our protagonist must overcome to reach their goal, as everything gets more complicated and unpleasant. In the middle of this act (and exactly halfway through the book), is the midpoint. This can be either a moment of revelation, or a conflict that serves as the beating heart of the story. It often causes a change—with the protagonist struggling and failing at many of the challenges that come before the midpoint, and increasingly succeeding afterwards. Act Two generally ends in disaster, when something cataclysmic and terrible happens.

Act Three. During the final quarter of the book, everything starts to ramp up. The challenges come thick and fast, and our protagonist’s goal seems further and further away. Here’s where we start taking away their time: one thing happening after another, interrupting their plans, and forcing them to act before they’re ready. It all comes to a head during the climax, where the protagonist faces their greatest challenge and either overcomes it or fails. They may achieve their goal, lose it forever, or choose to sacrifice it for something more important. Either way, that goal is done and dusted by the end, giving the story a sense of completion.

To follow up on our example with Evangeline, her story might look something like this:

Act one

We meet Evangeline while she’s fighting with a group of elite mercenaries. They are in the heat of battle, and her hot-headedness both gets them into trouble and ultimately saves the day. Returning to the inn, she receives a letter from her sister Mercy, but doesn’t read it. She has more important things to worry about right now.

Evangeline and her mercenary gang are employed to deal with a gang of smugglers, and they’re close to fulfilling their contract. However, when they finally confront their targets, it all goes horribly wrong. Wild magic rips through the battlefield, killing almost all of Evangeline’s war band. Wounded and broken, she tries to drink herself into oblivion, and is only pulled out of her despair when she discovers her sister has gone missing. Plagued by guilt and desperate for purpose, Evangeline decides she’s going to find Mercy—and will stop at nothing until she does.

Act two

Returning to her hometown, Evangeline meets with an old friend, who’s also the last person who saw Mercy before she vanished. Convinced that he’s hiding something, Evangeline follows him. She ends up in a nasty part of town where she’s set upon by robbers, but she doesn’t let that stop her. Convinced the friend knows something, she threatens and bullies him until he admits the truth: Mercy was dealing with a group of cut-throat bandits before she vanished.

Unfortunately, when Evangeline follows up on this, she’s captured by the bandits and badly injured by the time she manages to escape—stranded in the middle of a desert with a broken ankle. However, she’s learned something important: these bandits are working with a mage. Someone using the same wild magic that destroyed her mercenary band. Delirious and dehydrated, her trudge across the desert serves as the story’s midpoint. Finally making it back to safety, Evangeline has been humbled and knows she’ll have to plan carefully if she’s going to find out more about these mages.

In the second half of this act, she starts gaining ground. Tracking down an archivist named Tobias, she finds out that that the mages have bribed and blackmailed into doing their bidding. They form an unlikely team, uniting to find Mercy and free Tobias from the mages’ clutches. Following one of the mages back to their stronghold, Evangeline discovers the mages are cultists, trying to resurrect a dead god.

Ambushing the cultist, they find out that Evangeline’s sister has unique magical powers which the cult needs to achieve their own goal. Enlisting the help of one of the surviving members of Evangeline’s mercenary band, they plan to infiltrate the stronghold, but everything falls apart at the last moment. Her old mercenary friend betrays her (and was working for the cult all along), Tobias is murdered, and Evangeline taken captive.

Act three

In many ways, Evangeline is back where she started in Act One: wretched and miserable, having lost everything. But her experience in the desert changed her, and rather than giving up, she’s now more determined than ever—driven to find her sister and avenge Tobias’s death. She learns that the cult is planning their final ritual during the upcoming eclipse, and she only has days left to rescue her sister and stop their kingdom from falling.

Escaping the stronghold, starved and injured, she tries to reach the stone circle where the ritual will take place, dealing with assassins that are sent after her and a flash flood that washes away the road she needs to follow. She finally makes it in time, only to discover something awful: Mercy isn’t an unwilling prisoner, she’s a fully committed member of the cult, and Evangeline has fallen right into her trap.

Mercy needs Evangeline’s own latent magical power to complete the ritual, but Evangeline refuses to yield. Fighting back valiantly, she fouls up the cult’s ritual at the last moment. As a result, the ancient god doesn’t fuse fully with Mercy, but creates a half-god abomination. At the climax of the story, Evangeline fights, fails, and fights again—ultimately sacrificing her sister to kill the god and save the kingdom. Having paid the ultimate cost, she returns to her family to break the news and help them rebuild their lives.

Bringing the Story to Life

The above example is only a very rough idea, using a very particular brand of adventure fantasy, but notice how following the three-act structure helps to give the novel a clear sense of identity. There is a defined central conflict, plenty of forward momentum, and a satisfying conclusion—wrapping up everything we introduced in the first act and developed in the second.

This helps create the underlying rhythm our readers will expect, even if they don’t realize it. It also ensures our pacing stays consistent, with a mixture of dramatic action scenes and quieter moments of reflection and companionship to keep the reader invested.

Once we have this, the only thing left to do is to make the story come alive moment-by-moment. We do this by echoing the same process for each scene: making sure they follow the same unspoken patterns that draw our readers in and keep them riveted to the page.

We’ll be digging into that—and how to use scene structure to make your story sing—next week!

And if you’d like to learn more about the three-act structure in the meantime, I highly recommend K.M. Weiland’s excellent book, Structuring Your Novel.

✒️ Ready to transform your story from spark into flame?

Every month, I help speculative fiction writers refine their novels and honour the stories they most want to tell.

➡️ Click here to learn more about my developmental editing services.

I've heard about the three act structure before, but having that example broken down of Evangeline's story really clarified how it works.

This was such a helpful article for so many reasons. It helped affirm that my overarching structure for my novel works, fits nicely in the three act structure. On the flipside, it helped me realise that the scenes I have written thus far don't quite follow the same principles, and so likely wouldn't grip the reader as I need them to. Thank you for this!